Grading, Washing & Packing

Grading, Washing & Packing

This section identifies possible risks associated with the management, use and maintenance of egg grading, washing and packing equipment.

Machinery contamination

Equipment / surfaces in contact with eggs

Machinery and equipment used in egg grading, processing and washing introduce another layer of Salmonella contamination risk in cage, barn and free range egg operations.

Any bacteria present on the eggshell can transfer to surfaces it contacts and this can build-up over time. This occurs faster if:

- The surface has yolk spillage from broken or cracked eggs

- Moisture is present

- There is faecal or dirt contamination.

Salmonella bacteria can persist on many surfaces and materials, including plastic and stainless steel.

All plant machinery and equipment that has contact with eggs should be cleaned and sanitised regularly - at least once a week is advisable. Any visible yolk needs to be removed.

Effective options include dry cleaning and sanitising every day after grading, or complete wet washing and sanitisation weekly.

Egg grading floors that connect multiple hen housing facilities pose a high risk of cross-contamination of bacteria between sites and any portable equipment used, adjoining conveyor belts or shared vehicles require thorough cleaning.

The disease status of the grading floor is considered to be equivalent to that of the farms ‘dirtiest’ production shed and all through vehicles, personnel and egg handling equipment need to be cleaned and sanitised.

Using cardboard egg fillers are particularly risky for transfer of poultry diseases between egg grading, processing and washing facilities and poultry properties.

Alternative options include using sanitised plastic fillers or heat sanitised cardboard fillers.

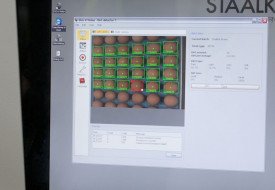

Automatic crack detector

Eggs that are visibly cracked or broken are prohibited from sale for human consumption and many poultry operators are installing automated technology to help with detection.

This allows them to rapidly remove these eggs from grading, processing and washing areas.

Eggshells can crack, micro-crack or fracture in many ways that are often un-observable. The most common cause is exposure to a sudden temperature change (cold to hot, or hot to cold).

Automatic crack detectors that are available to the industry are delicate instruments and require careful cleaning and calibration. The level of detection sensitivity when in operation depends on key factors such as hen age, flock health and eggshell thickness.

Automatic crack detectors that have surface contact with eggs are highly susceptible to bacterial contamination from both the eggshell and any internal egg content spillage from breaks or cracks.

Infected detectors then pose a high risk of cross-contaminating all subsequent eggs going through the device.

When cleaning and sanitising automatic crack detectors, manufacturers may advise against using wet cleaning chemicals. It may be preferable to use dry cleaning methods with a clean cloth or paper towel that is changed regularly.

Manual crack / default egg detection

Cage, barn and free range egg producers can adopt manual assessment methods to detect any cracked, broken or otherwise faulty eggs. This requires an operator to have acceptable training and the crack detection method must not compromise food safety.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) prohibits visibly cracked eggs for direct sale into human consumption markets.

It defines a cracked egg as one with a visibly cracked or broken eggshell, determined either by the human eye, a light source, candling or equally-robust method.

Candling involves passing eggs through a bright light or concentrated beam to check for cracks. When using this system, manual candlers need to ensure thorough hand washing and hygiene practices before and after handling eggs and other equipment. Using antibacterial gel can be particularly beneficial.

Staff undertaking manual crack detection should be rotated regularly to prevent fatigue, which can compromise their ability to detect cracks.

How regularly they swap depends on factors such as historical fatigue time, sight level and concentration span. The speed of eggs moving through the crack detection process should be adjusted according to the ability of the operator.

Vigilance is needed when handling eggs during this process to minimise risks of cross-contamination if a dirty, broken or cracked egg is touched before a clean or unbroken egg.

While it may not be feasible to clean hands after every touch of dirty eggs, washing is needed after handling leaking eggs. Well set-up grading, processing and washing facilities have adequate hand washing facilities in a convenient location for all staff.

Equipment in contact with unwashed and washed eggs

Robust food safety measures for all egg grading, processing and washing facilities should aim to prevent equipment contacting both washed and unwashed eggs.

It is particularly vital that washed eggs do not contact equipment or surfaces used for unwashed eggs, as the washed eggs can become easily contaminated.

This is because the cuticle of the eggs, and some parts of the eggshell, are vulnerable to removal during the washing process. This can increase the risk of bacterial contamination and penetration into the egg after washing if the washed egg comes into contact with a contaminated surface.

Contaminated egg stamping equipment

Some Australian states and territories require eggs to be individually stamped with the producer's unique identifier. This is typically a number or code.

Stamping helps food safety or health authorities trace eggs back to the farm or grading floor in the event of a food poisoning incident or outbreak. Eggs can be stamped at the farm where produced or processed, or at a separate grading facility.

In all cases, the egg stamping equipment needs to be well maintained and kept clean.

Inadequate grading processes can lead to cracked, broken or dirty eggs being presented at the stamping stage. This can contaminate equipment, which can then cross-contaminate clean eggs at the point where the stamp contacts the egg.

Dirty egg stamping equipment can also result in illegible stamps on the eggs.

It is recommended an appropriate cleaning schedule include a daily visual assessment of equipment and robust weekly cleaning.

Contaminated egg washing / grading equipment

All egg grading, processing and washing equipment needs robust cleaning and sanitising after every production period.

Any bacteria on the eggshell can easily transfer to this equipment, and other surfaces that have contact with eggs, and build-up over time. If yolk is present, bacterial load will increase more rapidly.

Research has found Salmonella can persist on many materials used in egg processing, including plastic and stainless steel.

If cleaning chemicals for equipment are adequate and verified, the washing process can be automated. A fit-for-purpose sanitiser can be used after cleaning and drying.

Any tanks that re-use water in this process also need to be cleaned after every production period to prevent bacterial and organic matter build-up.

Calcium from eggshells and any internal egg contents from broken or cracked eggs can block spray equipment used in cleaning or grading and interfere with the effectiveness of the washing chemicals. This can compromise the effectiveness of cleaning and sanitising process.

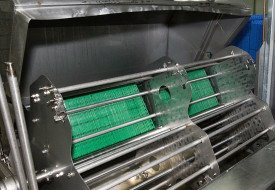

Contaminated suction cups / vacuum loaders in automated grading / washing machines

Suction cups and vacuum loaders used to transfer eggs through the grading and washing processes require vigilant and regular cleaning to minimise risks of Salmonella spread.

Inadequate pre-grading processes and cleaning regimes increase the risks of cracked, broken and dirty eggs going through the system. These can contaminate the suction cups, which can then contaminate other eggs that are free of Salmonella, or increase the load of Salmonella on affected eggs.

Suction cups are an ideal location to test for the presence of Salmonella on a grading floor, as these can have substantial bacterial build-up if not cleaned regularly.

An appropriate cleaning schedule may include replacing suction cups during egg processing with a spare set of suction cups and then putting dirty suction cups through a cleaning and drying process before re-use.

Dry cleaning

A regular dry cleaning schedule to remove dust and other extraneous matter from the shed and equipment can help prevent build-up of dirt on eggs, reduce hen infections and help limit overall Salmonella load in the hen housing.

Dry cleaning can involve sweeping or vacuuming and hens can be trained early to be familiar with the noises and movement associated with this cleaning.

Compressed air cleaning is another option to remove or reduce dust and organic matter build-up, but can increase bacteria spread through hen housing as compressed air tends to ‘aerosol’ the pathogens.

Compressed air cleaning

Egg grading, processing and washing equipment and surfaces are often not specifically designed for easy cleaning.

Compressed air cleaning systems are particularly useful in removing debris, such as dust, egg internal contents, dirt and faeces. Compressed air may also be useful for line clearance before equipment cleaning.

But it should be noted this method, however, can ‘aerosol’ – or spread by air – any Salmonella in the debris around the grading area and lead to egg contamination.

Care is needed when using compressed air for cleaning to ensure debris can be contained and then easily removed from the grading area.

There is considerable information about the risks of cross-contamination and spread of bacteria via compressed air cleaning in the medical field, but research for egg grading environments is limited.

Soiled and cracked eggs

Sale of cracked and or dirty eggs

The Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) code stipulates cracked, and visually dirty (soiled) eggs are unable to be sold to retailers or caterers for direct human consumption.

These eggs pose an increased risk of human illness from Salmonella, as pathogens can be present on the surface of dirty eggs in faeces, dirt, dust or other extraneous material. The bacteria can infiltrate the internal egg contents if the eggshell is cracked.

FSANZ has deemed these dirty and cracked eggs as ‘unsaleable’. But it should be noted that some stakeholders interpret the standard as having no cracked eggs at the time of delivery, not the time the eggs left the grading area.

Others reject shipments with cracked eggs, as these are prohibited for on-sale. This becomes a cost to the producer.

To help avoid the incidence of cracked and dirty eggs, it is advised to:

- Use appropriate transport and retail packaging

- Minimise handling and contact with equipment

- Implement robust cleaning and sanitising processes

- Reduce incidence of ‘floor eggs’ & these contacting other eggs

Eggs that are cracked, mal-formed or rejected for other aesthetic reasons can be used in the manufacture of egg products, such as pasteurised liquid egg. These are mainly targeted at the food service, hospitality and manufacturing industries.

Pasteurisation needs to be conducted by a licensed and approved egg processor.

Eggs destined for this market need to be stored at temperatures below 7°C to minimise Salmonella growth and processed as soon as possible after grading to minimise the time bacteria can grow.

Extraneous matter on the surface of eggs

Faeces, dirt, dust and other organic matter must be removed from the surface of eggshells, as these are potential sources of Salmonella and will prevent the direct sale of the eggs into human consumption markets.

This is a Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) requirement, given the risks posed by ‘dirty’ eggs going through the supply chain. But it should be noted state and territory legislation varies on this issue.

Faeces, in particular, are a reservoir for Salmonella and if this material has prolonged contact with the eggshell, there is greater potential for it to penetrate into internal egg contents.

This risk increases in the presence of moisture, especially if the internal egg temperature is higher than the ambient temperature. Inappropriate egg washing and grading practices can also promote transfer of bacteria into the egg.

Good management includes removing ‘dirty’ eggs during grading and before any washing process, as there is a high chance these eggs will be contaminated internally by that stage.

Wet egg cleaning methods

Wet cleaning and sanitising processes can increase risks of cross-contamination of clean eggs with dirty water and allow bacterial diffusion into the egg. This type of washing needs to be managed well and with a thorough understanding of the risks.

Some options may include automated washing machines. But these are typically designed to achieve a high recovery of first grade eggs and not to reduce bacteria load on the egg surface. Chemicals used in this process should be appropriate and applied according to the label.

There is some evidence washing can be performed at cooler temperatures without impacting on the microbiological quality of eggs, provided the wash solution temperature remains above the egg internal temperature.

Egg washing is not required in Australia, but sale of dirty eggs is prohibited under FSANZ Standards

Dry egg cleaning methods

A ‘dirty’ egg is considered to be one that has visible faeces, soil or other matter on the shell. Dry cleaning methods can be effective in removing this undesirable material and reducing potential bacteria contamination.

If dirty eggs are a persistent problem during grading and processing, it is advised to implement a cleaning program using dry paper towels or cloths to remove extraneous matter. But these need to be changed frequently and when they become wet or dirtied with faeces.

Dry cleaning methods are effective for small marks of dirt or faeces. But it is recommended dirty eggs that are then cleaned are not recovered for A-grade egg sales, as there is a high chance they may be internally contaminated.

It is important to avoid using wet cloths for this cleaning, as the moisture encourages growth of bacteria that can be transferred to hands, other eggs or surfaces. This can also facilitate bacteria movement inside the egg.

Using ultraviolet (UV) technology is another dry cleaning option to help reduce bacterial contamination. But it should be noted this may not be effective in destroying pathogens present in organic matter on the eggshell, in all cases.

Post-washing products for cleaning, such as oil or other food grade waxes, tend to have variable efficiency in maintaining egg quality by preventing water loss and reducing porosity of the eggshell, which can help to reduce the risk of Salmonella entering the egg. There may be scope to use a sanitiser as part of this process.

Presence of water / moisture on eggs

Eggs must be kept dry at all times during grading and processing, except during any strictly controlled washing process.

Salmonella can move into the egg if there is prolonged moisture. The rate of pathogen penetration is determined by the quality of the eggshell and cuticle.

Cooling systems should not allow eggs or equipment that contacts eggs, to get wet or produce condensation (referred to as ‘sweating’). This is important because the diffusion of bacteria into the egg can occur due to differences in density or pressure resulting from big temperature differences between the internal egg content and the outer environment.

An egg is laid at a temperature of about 41°C. If it is laid into a wet environment or on to a wet floor - or has contact with water at a lower temperature to its internal contents - the result is bacteria transfer from the outside to the inside of the egg.

Eggs laid on to wet floors should be discarded and not graded for human consumption. Eggs laid on dry floors should be processed, cleaned and dried separately to eggs laid elsewhere to minimise the chances of cross-contamination.

These eggs have a much higher risk of bacteria present on the shell and internally due to longer contact with moisture, dirt, dust and faeces.

After grading, processing and cleaning (if needed), all eggs should be slowly cooled to final storage temperatures and not subjected to big temperature fluctuations.

When the eggs reach final storage temperature, the cold-chain should be maintained to limit condensation on the eggs.

Egg conveyors must be covered at all times, especially if part of it is outside, to ensure rain does not affect the eggs.

Presence of yolk

Grading and processing operations need to avoid any yolk cross-contamination risks from broken and cracked eggs to other eggs in the facility.

Some salmonellae grow rapidly in egg yolk, at a much higher rate than in whole eggs (at all storage temperatures that have been researched).

It is particularly important that yolk is not present on equipment that has regular or sustained contact with eggs, such as conveyors, sorting tables and grading machinery.

To minimise risks, it is advised to maintain a robust cleaning and sanitising regime for all equipment and facilities when grading and processing eggs.

Leaking and grossly dirty eggs

Minimising biosecurity risks for Salmonella requires removing any broken, cracked or dirty eggs from the whole grading and processing operation as quickly as possible.

A cracked egg is defined as having cracks that are visible to the eye, by candling or equivalent methods. Dirty eggs are those deemed ‘unacceptable’ due to external contaminants, such as faeces, dirt, moisture and dust, on the eggshell.

Leaking and grossly dirty eggs pose a high risk of bacterial cross-contamination to other eggs, grading and processing surfaces, equipment or conveyor belts. Faeces and egg yolk, in particular, are ideal growth mediums for Salmonella and can act as a reservoir for bacteria.

The FSANZ standard says ‘An egg producer must not sell or supply eggs or egg pulp for human consumption if it knows, ought to reasonably know or reasonably suspects, that the eggs are unacceptable’.

Leaking and grossly dirty eggs are likely to be internally contaminated with any bacteria before grading and need to be rapidly removed from the grading line for separate processing. This will help minimise Salmonella contamination across the entire grading process.

Historical research indicates cracked eggs alone do not have a higher risk of spoilage than non-cracked eggs when washed in clean water. But inappropriate washing and management of washing processes can substantially increase the spoilage rate of cracked eggs, compared to non-cracked eggs. More research is needed for this under current commercial practices.

Several risk assessment studies conducted by industry have concluded that cracked eggs pose a high risk of human salmonellosis if consumed.

Grading area management

Grading area management

Egg grading floors and processing operations introduce another category of biosecurity risk for commercial poultry operations and require best-practice management.

These facilities are often shared by several sheds that use conveyor belts or internal vehicles to aggregate eggs. This creates a potential high-risk disease status, equivalent to that farms dirtiest production shed, and can increase the potential for pathogens, such as Salmonella, to be transferred between properties.

During grading, many processes can lead to cross-contamination of eggs, bacterial build-up and bacterial proliferation.

It is essential to have protocols for these processes to minimise chances of Salmonella bacteria contaminating eggs. Recommendations include:

- Sanitising any portable egg handling equipment used for grading and processing before it is returned to the shed – including egg handling equipment, such as fillers, trolleys and pallets as well as any

- Cleaning and sanitising vehicles

- Follow good hygiene for personnel

Operations that include egg grading are considered to be processors and need to be familiar with the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) standards 4.2.5 and 3.1.1.

Egg producers need to understand food safety requirements under state and federal legislation. Some states and territories have imposed additional requirements and it is important to adhere to these where relevant.

Grading area cleanliness

Egg grading areas should be cleaned and sanitised regularly to prevent potential introduction of disease agents, contaminants and pests, such as rodents, wild birds and other animals that can be Salmonella vectors.

It is important to target areas and surfaces most likely to contain bacteria, including equipment, walls and floors.

High traffic areas can have a high bacterial load, which is an important consideration for egg and staff flow to minimise cross-contamination risks.

Cleaning and sanitising products need to be effective and compatible and an appropriate cleaning schedule needs to be in place. This could be as regularly as once every week for surfaces that do not contact eggs, and more often for those that do.

Temperature and humidity control on the grading floor

Environmental conditions and fluctuations can have a significant impact on egg quality, so it is vital to ensure temperature and humidity are well controlled in the grading area.

This will help to suppress bacterial growth and reduce chances of condensation forming on eggs from inappropriate humidity control. Condensation can increase potential for diffusion of bacteria from the eggshell into the internal egg contents.

Grading areas that cannot or do not have an electronically-controlled environment should be assessed for quality issues during periods of varying temperature or humidity, such as when seasonal conditions change.

Electronically-controlled environments may also need checking when there are changes in seasonal conditions, as the layout of the grading area can impact on the efficacy of the environmental control.

Appropriate humidity levels depend on ambient temperature and climate conditions and typically, 65-70 per cent humidity is considered acceptable. Survival of Salmonella bacteria tends to increase at lower humidity than high humidity.

Insects and rodents

Infectious agents and pathogens can enter egg grading and processing facilities from vermin, especially rodents, insects and other animals.

It may be necessary to use baits as part of an integrated pest management plan to control and minimise the impact from these vectors.

Bait stations need to be distributed across facilities at regular intervals and more are needed where there are visible signs of strong rodent activity.

Bait stations should be numbered and mapped to facilitate weekly checking and re-filled with fresh bait ingredient as required.

It is best-practice to maintain a record of each inspection, pest activity and bait active ingredients used. Bait stations should be secure, tamper-proof and unable to be accessed by other mammals, native wildlife or birds.

Other pest control measures in grading and processing areas can include trapping and sonic sound aversion systems.

To minimise the build-up of vermin and insects, such as rats, mice, flies, beetles and cockroaches, in egg grading and processing facilities, it is advisable to have good drainage internally and in the surrounding area. Avoiding any water pooling or stagnation will also help reduce insect breeding.

Grading area staff training

Egg grading and processing staff need to be trained in food safety and food hygiene as a minimum, and it is advised at least one regular staff member is made responsible as a food safety manager.

This is a high priority under the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) code.

It should be noted that various State and Territory Government jurisdictions in Australia interpret the FSANZ standards differently. State and territory government legislation will reflect this and it is important egg farmers are familiar with the laws in their region.

Staff who are aware of the risks of Salmonella and its impacts will be able to pro-actively help to manage risks during production and processing.

Grading areas pose a high risk for Salmonella growth due to the likely presence of yolk (from broken eggs) and organic matter from the eggs being transferred on to surfaces, equipment, machinery and areas that may not be cleaned regularly.

There is a risk of humans being infected with salmonellosis from eggs that are handled improperly during grading (and washing if performed), as Salmonella can proliferate to levels causing illness. This can impact on business reputation and profitability.

Staff should be encouraged to continually monitor and assess tasks to identify areas for improvement leading to better food safety.

Humans also pose a risk of Salmonella contamination to eggs and egg grading equipment, as the disease can persist in the gut and be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Particularly risky are any staff returning from international travel, due to the risk of Salmonella Enteritidis.

Any staff member who has an intestinal upset should not have access to the grading area. Other management tactics can include having a regular toilet cleaning schedule at the facility and ensuring hand washing and boot sanitising facilities are available and used.

Storage of eggs

Eggs stored in a cool room before grading and or washing

It is recommended eggs are stored at temperatures of below 15⁰C as soon as possible after collection and washed within four days of being laid.

Unwashed eggs, even those that appear visually clean, can harbour Salmonella and other bacteria on the eggshell. The longer Salmonella is in contact with the eggshell during production or processing, the more likely the bacteria will penetrate the egg through diffusion.

Eggs stored before washing should be checked to see how long it takes for internal temperature to reach the storage temperature. This can affect the growth of any bacteria that does get inside the egg.

Salmonella grows at temperatures higher than 7°C, so prolonged egg storage before grading and refrigeration boost the risks of bacterial loads building-up.

There is limited research available into the efficacy of using airflow systems to cool eggs. This is likely to depend on many variables that affect cooling efficacy in the storage room, such as:

- outdoor temperature and humidity

- size of cool room

- size and type of cooling unit

- number of eggs being stored.

Thermal cracking

Eggshells are vulnerable to cracks, micro-cracks, fractures or breaks that may not be visible to the human eye. This tends to occur if eggs are exposed to sudden changes in temperature (cold-to-hot, or hot-to-cold).

Evidence suggests a temperature change alone will not be sufficient to crack an intact eggshell. But if a hairline fracture or unobservable crack is present, it may lead to larger, visible cracks if the egg is subjected to a big temperature fluctuation (of about 20°C or more).

To help reduce the incidence of cracking, the temperature of the eggshell (not the internal contents) should be gradually increased to the washing temperature. This can be achieved through a pre-rinse step, using warm rinse water to warm up the eggs, which will also loosen any dirt or extraneous matter before the washing process and improve its efficacy.

Thermal cracking is typically most common in eggs stored in a cool room before washing or processing, or those that are chilled excessively in low ambient temperatures.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) prohibits the sale of visibly cracked eggs for human consumption.

Storage temperature of washed eggs

Washed eggs should be stored at temperatures less than 7°C, as there is a risk of Salmonella diffusing through the eggshell and infecting the egg internal contents.

The egg washing process damages the egg’s protective cuticle, and its antibacterial properties.

Egg washing is not required in Australia, but sale of dirty eggs is prohibited by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

Storing washed eggs below 7°C can help reduce the ability of Salmonella to grow. This means even if Salmonella is present on the eggshell, or able to penetrate into the internal contents, the bacterial load will pose less risk of human illness than if storage conditions promoted Salmonella growth.

Some research indicates Salmonella levels on eggshells will drop faster in refrigerated storage conditions, at temperatures of about 4°C, and not persist beyond about four weeks.

Studies suggest egg storage at room temperature increases the persistence of Salmonella on eggshells (although total bacterial count was reported to either remain constant or increase). But no Salmonella persisted past four weeks on eggs at any storage conditions during this research.

This indicates older refrigerated eggs may be at less risk of having Salmonella on the eggshell.

Antibacterial properties in the egg degrade over time, which means older eggs are at higher risk of Salmonella growth in the internal contents if processing or storage conditions have enabled the bacteria to penetrate the eggshell.

Many factors affect the ability of Salmonella to penetrate into eggs, including length of time it is been on the eggshell.

Salmonella persists longer at lower temperatures in the internal contents of the eggs, but typically it won’t grow. It will grow when there are fluctuations in storage temperature.

Dirt, faeces, feathers, dust or other extraneous matter on the eggshell significantly increases Salmonella persistence and eggshell penetration.

Risk assessment studies for Salmonella Enteritidis control have shown keeping retail storage temperature at 7.7°C or less can reduce risks of human illness per serving by about 60 per cent.

In 1991, the USA amended its regulations to mandate that shell eggs for consumption must be kept at temperatures no more than 7.2°C after leaving the grading area. In 2000, it expanded this requirement to all retail establishments, other sales outlets for eggs and businesses that use eggs to produce food for immuno-compromised individuals.

A risk assessment of the Australian egg industry in the control of Salmonella Typhimurium came to similar conclusions to overseas research. It showed refrigeration of eggs after processing and during wholesale and retail storage could substantially reduce the risk of human salmonellosis.

This option appears to be the best for minimising risks of disease compared to other strategies. It would also help to protect the Australian egg industry in the case of a Salmonella Enteritidis outbreak.

Inadequate airflow in cool room storage

Sufficient egg storage facilities should have adequate airflow around the pallets of eggs and the entire facility.

It is important to reduce the temperature of all eggs to the cool room temperature as fast as possible. This could be achieved by using fan units.s

Over-stacking the cool room can reduce the efficacy of the cooling system. This risks eggs in the centre of the pallet, especially, not reaching storage temperature quickly – if at all.

It is advised to allow space between pallets or stacks of eggs in the cool room to assist effective air flow.

Producers are best advised to check how long it takes for eggs to reach the cool room temperature. This is particularly important for unwashed eggs that may contain dirt, faeces, features dust or other potentially contaminated material on the eggshell, as Salmonella will continue to grow until temperatures are below 7°C.

Graded and ungraded eggs must be clearly separated if they are not able to be stored in a separate cool room. Separating these eggs is ideal to prevent the risk of the airflow becoming contaminated and contaminating the washed eggs.

Unclean / ineffective cool room / cooler unit

Cool rooms used for egg storage need to be regularly and thoroughly cleaned and sanitised, at least twice each year.

Producers are advised to ensure the cool room is dry before eggs are stored there again after cleaning.

It is particularly important to carefully clean and monitor areas where dirty eggs have been regularly stored. This can prevent bacterial build-up and possible contamination of clean eggs.

Regular cleaning of the fan units is recommended to reduce the risks of Salmonella being continually cycled around the cool room if the unit becomes contaminated with bacteria. This can occur if the air intake is from an area that may be contaminated with Salmonella.

It is also important to make sure water from the cooler unit does not pool or splash near eggs, exposing them to prolonged moisture that encourages bacteria growth.

Egg containers / packaging

Egg packaging

Packaging material, including cartons, needs to protect eggs from expected and potential disease transmission and mechanical-type traumasthat can occur during transport and storage.

It should be able to withstand potential incursion from:

- Bacteria and other pathogens

- Temperatures that can cause egg content deterioration

- Possible mechanical stressors

- Natural poultry predators

- Loss of moisture

- Tainting

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) standards do not allow the sale and supply of cracked and dirty eggs. Some industry stakeholders or customers might interpret this as having no cracked eggs at the point of delivery, not at the time the eggs left the grading area. Others may reject shipments that contain cracked eggs, as these are prohibited for sale for human consumption.

It is recommended to assess retail packaging carefully for its robustness in transport and storage on a shelf. It is also advised to minimise handling eggs during grading, processing and storage areas used for retail or bulk purchase.

Plastic fillers

Plastic fillers used in cage, barn and free range egg grading and processing facilities are a lower risk option for potential Salmonella contamination than using cardboard fillers.

But, for optimal effectiveness, plastic fillers require proper cleaning and sanitising practices after every use.

Salmonella can form a biofilm, or bacterial protective ‘coat’, on plastic in unfavourable conditions.

Some research indicates not all cleaning and sanitising processes are able to satisfactorily remove bacterial biofilms.

To reduce risks, organic material should be removed from plastic fillers before eggs are placed in them.

Robust cleaning and sanitising will also help to eliminate other pathogens that can be found on plastic fillers. This reduces the chances of fillers contributing to disease transmission from farm-to-farm or flock-to-flock.

Different coloured plastic fillers may also be used to identify different sheds, or production types.

Cardboard fillers

Cardboard fillers used during egg grading and processing should ideally be discarded after every single use, as these are absorbent and can retain bacteria and other organic material for prolonged periods.

Any bacteria persisting on eggs is easily transferred to its packaging and re-using any contaminated cardboard fillers poses a high risk of infecting new eggs put in the filler. The problem is exacerbated in moist conditions, in which bacteria can grow and contaminate eggs.

Use of cardboard egg fillers is also a particularly high-risk practice, with potential to transfer poultry diseases between properties.

If an operation has multiple properties that share a grading or processing floor, it is advised to use either sanitised plastic fillers or heat-sanitised cardboard fillers.

Egg washing and drying

Egg washing

Washing and sanitising eggs to remove any dirt, faeces or other extraneous matter can help reduce any potential Salmonella load in the through-chain for cage, barn and free range production systems.

But this process risks cross-contaminating eggs from dirty water, which can allow bacteria to penetrate into the egg internal contents.

Egg washing needs to be set up with a good understanding of this hazard and how to minimise risks. Not using wet washing is better than using a poor system for wet washing.

Although egg washing is not a requirement in Australia, sale of dirty eggs is prohibited by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

Any washing and sanitising process needs to reduce bacterial load on the eggshell, as visibly clean eggs can still be highly contaminated with Salmonella.

Automated washing machines are a good option, as these are designed to have a high recovery rate of first-grade eggs.

Washing solely with water can reduce the bacterial load on the eggshell, but is not as effective as washing with chemicals. The chemicals used in the process should be at appropriate concentrations and monitored to ensure they are active.

There is some evidence that washing at cooler temperatures does not impact on egg microbiological quality, if the wash solution temperature remains above the internal temperature of the eggs.

Ultraviolet-based (UV) cleaning systems are another method that can help reduce bacterial contamination. But the effectiveness in destroying bacteria within visible matter on the egg will be limited.

Inappropriate wash cycle

Wash cycles need close monitoring to assess the effectiveness of reducing Salmonella loads on eggs during processing.

Washing can damage or remove the protective cuticle of the egg, which increases the risk of bacterial transfer into its internal contents.

Wash water temperatures are critical to prevent any bacteria in dirt, faeces or other extraneous material on the eggshell being diffused into the egg. To avoid this, the wash water temperature needs to be higher than the internal temperature of the egg.

Any chemicals used in this process should be applied at appropriate concentrations to ensure these are active and carefully monitored (verified).

Eggs cannot remain standing in any solution for prolonged periods, as the eggshell will immediately start to equilibriate to the temperature of the solution.

Inadequate / incompatible egg washing chemicals

Egg washing chemicals used during processing must be fit-for-purpose, applied according to label instructions and regularly tested to ensure they are active.

The chemical concentration is important. Based on a recommended water temperature of more than 40°C and a pH of more than 10, the use of a chlorinated alkaline detergent with a minimum total available chlorine concentration of 0.45mg/l has been recommended.

The risk is the chemicals will be diluted by:

- Re-using water

- Washing sanitiser into re-used wash water

- Other water recycling methods.

Chemical levels should be closely monitored, as frequently as every 30 minutes in some cases, to verify that the washing process is still effective. A simple method is the use of chemical test strips.

Water pH level is not an accurate measure of chemical activity or presence during the egg washing process. Other factors, such as calcium from eggshells or other organic matter from faeces or dirt, can impact on pH levels.

Studies have found temperature control and pH is insufficient to control bacteria in egg washing water.

Inadequate temperature during egg washing

To minimise risks of diffusion of bacteria into internal egg contents as a result of washing and cleaning processes, it is recommended the temperature of each solution is higher than the previous solution in the washer.

The temperature of the water, wash solution and sanitiser needs to be measured on the eggshell surface, as diffusion results from temperature differences.

Diffusion occurs from lower temperature areas, towards higher temperature areas.

Therefore, external applications of water, wash solution or sanitiser to the egg need to be hotter than the internal egg temperature so that diffusion is from inside the egg (cooler) to outside (warmer).

To help ensure this, it is advised to gauge the internal temperature of eggs going into the washing process as a start point, as this may not reflect the storage temperature.

Then the temperature of each solution applied to the eggs must be higher than the temperature of the process before and measured at the egg surface.

When using automated washing or cleaning systems, it is advisable to adjust the temperature of the wash solution in the tank to account for any loss of temperature during spraying or other applications to the eggs.

It should also be noted that rapid increases in temperature can, however, induce thermal cracking.

Studies and experience have found the temperature on the eggshell can be up to 10°C less than the temperature in the tank.

Damaged and dirty brushes in the washing process

Brushes used in the egg washing process are best checked at the start of each run day to ensure this equipment is effective, clean and does not need replacing.

Brushes can wear, tear and lose the ability to agitate the wash solution for brushing the eggs.

Continual use can also shape the brushes to match the shape of the eggs, which limits the efficacy of removing dirt and debris from the eggs.

Brushes should be kept clean, as any broken eggs that go through the washing machinery can leave internal material or eggshell pieces on the brushes. This can coagulate with the heat of the wash solution and become a potential source of bacterial build-up.

Damaged / blocked / unaligned egg washing machine nozzles

Equipment nozzles and other machinery parts used during egg washing and sanitising should be checked regularly to ensure optimum operating efficacy.

Nozzles can get damaged or be placed incorrectly, leading to spray applications that do not totally cover the eggs.

This may result in ineffective washing processes, which can be a significant risk for bacterial transmission.

Nozzles can also get blocked and this should be monitored before every processing run, along with checking correct alignment.

Washing and grading machine / process stoppages / pauses

Procedures are needed to make sure eggs are kept in the washing or sanitising system for the optimal amount of time to be cleaned, without the internal contents equilibrating to the temperature of the water, any wash solution or sanitiser. This minimises risks of bacteria diffusion into the egg.

It is recommended to have inter-connected stopping mechanisms for washing systems. This means if the process needs to pause or stop, eggs are not left standing in the washing machine in prolonged contact with water or sanitiser.

Eggs may need to be discarded if they are subjected to a single solution for too long, as internal contents can be contaminated through diffusion into the egg in these conditions.

It is advised to check the acceptable and ‘safe’ stoppage time for each type of washing system.

This can be done by measuring the internal egg temperature when held in a heated process at different lengths of time.

During breakdowns or during breaks in processing, it is important to clear eggs from the grading floor, washing system or grading machine to keep them at an appropriate temperature. Eggs should not have prolonged contact with water, solution, heat or contaminated surfaces.

Inadequate and / or unclean egg dryers

Egg dryers used during processing require regular assessment of their position and condition to ensure their efficiency in drying eggs. Regular assessment also needs to be done to ensure the air intake for the system is not contaminated, or draw air from a suspected contaminated area.

Air intake systems may need a filter and should be regularly checked and cleaned, in poor condition, these also can be a source of airborne bacteria. This is particularly risky for eggs that have just been washed, as washing increases susceptibility to external and internal egg bacterial contamination.

Eggs must be dried after wet washing, as moisture on the eggshell facilitates diffusion and growth of bacteria into the egg internal contents.

Dryer temperature needs to maximise the drying capabilities of the air by raising the temperature or reducing the humidity, or both.

Air temperature can affect the efficacy of egg drying and should be higher than the temperature of the last process to ensure diffusion of bacteria into the egg does not occur. It is recommended the system also dries the egg conveyor, as a wet conveyor can wet the eggs again after drying.

This process needs close monitoring to ensure it is drying eggs, without contaminating them.

Use of a terminal sanitiser on eggs and equipment

Egg washing removes the protective cuticle and part of the eggshell, leaving the egg vulnerable to re-contamination through the supply chain.

If an operator uses a terminal sanitiser as an alternative, it should be noted this is not washed off after application and has a residual sanitising effect.

If using terminal sanitiser, the egg internal temperature needs to be below the sanitiser temperature so there is minimal risk it can be drawn into the egg under negative pressure.

Anecdotal evidence and some research indicates the residual effect of registered sanitisers for eggs is no longer than 10 minutes.

Terminal sanitisers can also be used to sanitise equipment that comes into contact with eggs on a regular basis, such as at the end of every processing run. These are to be applied between scheduled thorough cleaning regimes.

This can help to reduce the bacterial load on equipment, especially surfaces regularly in contact with eggs.

Terminal sanitisers are used routinely and are approved by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority for increasing the hatch rate in hatching eggs. These sanitisers have been proven to reduce the bacterial load and bacterial penetration into the hatching eggs.

Repeated cycling of dirty eggs thorough the egg wash process

Eggs that remain contaminated with dirt, faeces or other material should be removed to avoid continual cycling through the washing and sanitising process.

To clean dirty eggs, it is best to use a washing solution that has the right amount of active ingredient. If this is incorrect, clean eggs are at higher risk of cross-contamination from dirty water, bacterial diffusion to internal contents and movement of Salmonella.

No wet egg washing is better than poor wet washing, so this must be done with extreme care and a thorough understanding of the risks.

Egg washing is not required in Australia, but sale of dirty eggs is prohibited under Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) requirements.

A good option for cleaning dirty eggs is an automated washing machine system designed to produce a high recovery rate of first grade eggs.

If the egg washing process is not removing visible organic matter from the eggshell, either the process is not adequate or the egg may be beyond cleaning for human consumption.

The maximum number of times the egg should be allowed to cycle through the process depends on the cleaning efficacy and set-up. But, given that internal contamination is highly likely in dirty eggs, it may be best if these eggs do not cycle at all.

If eggs remain dirty after one repeated cycle, it is recommended they are removed from processing. These could be used in egg pulp and pasteurisation.

Any continual egg cycling through a washing process will tend to damage the eggshell and remove the protective cuticle, exposing the egg to bacterial diffusion and other equipment to contamination from spillage of internal egg contents.

Also, the more times an egg is cycled through the washing process, the higher the internal temperature will get. If the internal temperature is equal to, or higher than, the temperature of the wash solutions, this can lead to diffusion of bacteria to internal contents.

>

>